Leading expert in gastroenterology and hepatology, Dr. Sanjiv Chopra, MD, explains how meticulous patient history and clinical observation are fundamental to accurate diagnosis, illustrating this with two remarkable case studies: one of milk-alkali syndrome misdiagnosed as gastrointestinal bleeding and another where a severe tick-borne infection inadvertently cured a patient's chronic Hepatitis C.

The Critical Role of Patient History in Accurate Diagnosis and Unexpected Cures

Jump To Section

- The Art of Listening in Medical Diagnosis

- Case Study: Uncovering Milk-Alkali Syndrome

- A Diagnostic Breakthrough Through Detailed History

- Case Study: An Unexpected Hepatitis C Cure

- Mechanism of Viral Clearance

- Learning from Patients and Documenting Discoveries

- Key Clinical Takeaways for Physicians

The Art of Listening in Medical Diagnosis

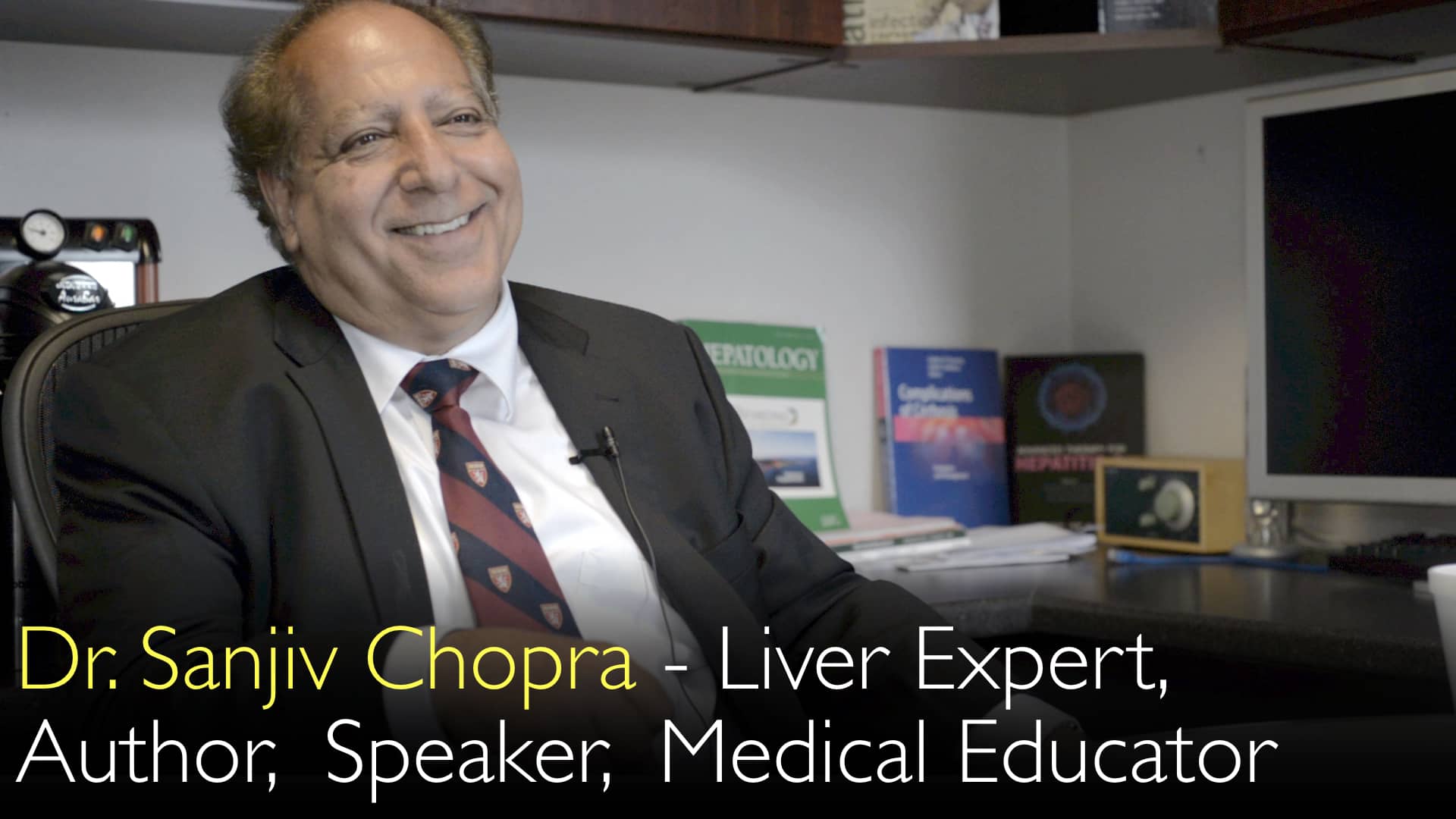

Dr. Sanjiv Chopra, MD, a renowned Professor of Medicine, emphasizes that one of the most critical skills in medicine is being an excellent listener. He notes the common tendency for physicians to interrupt patients because they are rushed for time or are already formulating a differential diagnosis. This can lead to missed clues that are essential for an accurate diagnosis. During his interview with Dr. Anton Titov, MD, Dr. Sanjiv Chopra, MD, highlights that taking a thorough and patient history is often the key to solving complex medical puzzles, a principle powerfully demonstrated in the clinical cases he shares.

Case Study: Uncovering Milk-Alkali Syndrome

Dr. Sanjiv Chopra, MD, was consulted to perform a colonoscopy on a patient in his 50s who presented with iron deficiency anemia and guaiac-positive stools, indicating gastrointestinal bleeding. The patient was also under the care of endocrinology for hypercalcemia and nephrology for renal failure. The initial assumption was a colonic source of bleeding. However, instead of proceeding directly to the procedure, Dr. Chopra conducted a meticulous history. He asked detailed questions about abdominal pain, stool changes, and family history, all of which were negative. When he shifted focus to the upper GI tract, he discovered the patient consumed six rolls of TUMS (a calcium-based antacid) and two gallons of milk daily.

A Diagnostic Breakthrough Through Detailed History

This massive calcium intake immediately pointed Dr. Sanjiv Chopra, MD, toward the correct diagnosis: milk-alkali syndrome. This condition, caused by excessive ingestion of calcium and absorbable alkali, explained the patient's entire clinical picture—hypercalcemia, renal failure, and bleeding from esophagitis rather than the colon. An upper endoscopy confirmed severe esophagitis with ulcers and early Barrett's esophagus, a pre-cancerous condition. This case underscores how a detailed patient history, rather than jumping to tests, prevented an unnecessary colonoscopy and correctly identified a serious but treatable disorder.

Case Study: An Unexpected Hepatitis C Cure

In a second remarkable case, Dr. Sanjiv Chopra, MD, was following a patient with mild chronic Hepatitis C. At the time, treatment options were limited to interferon-based regimens with only a 30% cure rate, so Dr. Chopra advised monitoring. The patient was later admitted to the ICU after a trip to Martha's Vineyard, critically ill with hemolysis. Infectious disease specialists diagnosed him with three concurrent tick-borne illnesses: Lyme disease, Ehrlichiosis, and Babesiosis. While fighting for his life, an unexpected miracle occurred.

Mechanism of Viral Clearance

As the patient battled the severe infections, junior doctors alerted Dr. Chopra that the patient's chronically elevated liver enzymes had suddenly normalized. Suspecting a lab error, Dr. Sanjiv Chopra, MD, ordered repeat tests and a Hepatitis C viral load measurement. The results were confirmed: his liver enzymes were normal and his Hepatitis C RNA was undetectable. Dr. Chopra hypothesized that the massive immune response mounted to fight the three tick-borne infections—a powerful endogenous interferon release—had inadvertently cleared the Hepatitis C virus, which is an RNA virus susceptible to interferon. The cure was permanent, confirmed over subsequent follow-up visits.

Learning from Patients and Documenting Discoveries

Dr. Sanjiv Chopra, MD, stresses the importance of learning from every patient encounter and documenting unusual clinical outcomes. He published the case of the spontaneous Hepatitis C cure to contribute to medical knowledge, noting that similar phenomena have been observed where an acute hepatitis A infection can clear chronic hepatitis B. He cautions against dismissing such events as mere anecdotes, arguing they can provide profound insights into disease mechanisms and potential treatment pathways. This philosophy of attentive observation is a cornerstone of advancing medical practice.

Key Clinical Takeaways for Physicians

The two cases presented by Dr. Sanjiv Chopra, MD, during his discussion with Dr. Anton Titov, MD, offer powerful lessons for all clinicians. First, the art of history-taking is irreplaceable and can reveal diagnoses that multiple specialist consultations and planned procedures miss. Second, medicine is filled with surprises, and careful observation can lead to discoveries that challenge conventional understanding. Ultimately, the patient is the best source of information, and listening to them carefully remains the most fundamental diagnostic tool in a physician's arsenal.

Full Transcript

Dr. Anton Titov, MD: Renowned Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School tells a great diagnostic story of his patient with intestinal bleeding. A second story how a tick bite infection cured another patient’s Hepatitis C. You are a prominent liver expert and professor at Harvard Medical School. Is there a clinical case, a story of a patient from your practice, that can illustrate some of the topics that we discussed today?

Dr. Sanjiv Chopra, MD: There are so many interesting stories to tell about patients. One of the key things in medicine is for us to be very good listeners. To take a very good history. We have the tendency to interrupt, because we are formulating a differential diagnosis. We are rushed for time.

Patient is sitting there and has gastrointestinal bleeding and we have been consulted to maybe do endoscopy or colonoscopy. Patient is anemic. You can do a quick history, physical examination and then schedule the patient for colonoscopy or EGD.

Some years ago I got consulted—I was covering the gastroenterology service at that time as well—and we got consulted to see a patient for colonoscopy. He is 50-some years of age, he's got mild iron deficiency and guaiac-positive stools.

The student goes and sees the patient. The gastroenterology fellow went and saw the patient. Then they presented to me. Then I go and make rounds. I discover. They've told me this, that the patient also has hypercalcemia. Therefore endocrinology service is seeing him. The patient also has renal failure, so nephrology is also seeing him. It turns out these were very eminent consultants, who were seeing him.

I go to see him and I am trying to figure out, where is he bleeding from?

Dr. Anton Titov, MD: So I'm taking a detailed history. "Any abdominal pain? Any change in the color of your stools? Any constipation and what is the caliber of the stools? Any family history of colon cancer? Have you ever had a colonoscopy? Barium enema?" All of that is negative, negative, negative.

Then I focus on the upper gastroenterology tract. So I ask him, "How's your appetite? Any early satiety? Can you eat a full meal? What's your favorite food? Sometimes I bring it in front of you will you be able to eat it?" "Yes, I'd be able to finish it."

Dr. Sanjiv Chopra, MD: I said to him, "Any heartburn?"—Now I'm thinking of esophagitis and he says, "Yeah, little bit." I said, "What do you take for it?"—he said, "Nothing really."

I said, "Do you take any TUMS, Rolaids, Alka-seltzer?" He said, "Yeah, I take some TUMS" [calcium-based antacid]. I said, "How many rolls?" he says, "Six rolls a day." I said, "What?! That's a lot of TUMS!" I said, "Do you drink milk?" He says, "Yeah I drink quite a bit of milk." I said, "How much milk?" It is like two gallons of milk!

I'm saying, "Oh, my God! This guy's taking in a ton of milk. A ton of calcium—he's got renal failure. He's got hypercalcemia—this could be Milk-Alkali syndrome!" instead of doing a colonoscopy we should do an upper endoscopy, because all his symptoms are related to the esophagus.

Sure enough he turned out to have milk-alkali syndrome. The renal people and the endocrine people changed their diagnosis. We proved it was milk-alkali syndrome. We did the endoscopy: he had roaring esophagitis with ulcers and with early Barrett's esophagus [pre-cancerous change in esophageal lining mucosa cells]. This can lead to carcinoma. But it was the art of history taking that helped out here.

We learn from our patients, but we have to listen to them. We have to spend time with them.

I had one patient, he had chronic Hepatitis C. He had a mild disease and at that time the treatment had [only] a 30% cure rate. So I said, "Listen, we going to follow you, there is no rush to treat this. This is a slowly evolving liver condition. There'll be better treatments coming down."

One day I come to the hospital and I get an email saying he's admitted to the ICU. That he is very sick.

I go to see him and he's being seen by hematology, he's been seen by infectious disease and it turns out that he's hemolyzing. He had gone to Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket, he got bit by a tick. The Infectious Disease people made three diagnoses: he had Lyme disease, Ehrlichiosis, Babesiosis. All three from a tick bite. He's very sick.

But the house staff junior doctors sent me an email two days later: "Dr. Chopra, his liver enzymes are normal for the first time." I said, "Really? They've been abnormal for 15 years I have followed them. Repeat the test, maybe it is a lab error. Also send off a Hepatitis C virus RNA levels by polymerase chain reaction, let's measure his viral load."

They repeat his liver enzymes and they are rock normal! He gets better, he's discharged, he's coming to my office 3 weeks later. I see him and that I said how are you doing? He said, "I'm getting better, I'm getting stronger." Then I look at the computer, and Hepatitis C virus is Negative.

I said to myself, "Maybe to fight the infections, the three infections he got, he mounted the most magnificent endogenous interferon response and it wiped out hepatitis C virus”. It is an RNA virus! Yes!

I said, "You know what? Let's test it again in six months. Your liver enzymes." In 6 months results are normal, negative virus, six months later—normal, negative. I said, "You are cured!" He says, "Dr. Chopra, is this a new treatment for hepatitis C? Tick bite?!"

We published it and there are rare cases of people with chronic hepatitis B who get superimposed hepatitis A. It knocks off the Hepatitis B virus.

We are learning in medicine every day. We are learning from our patients, we are learning by history-taking, we are learning by just observing and not passing it off as an anecdote. "Oh, this is an anecdote—forget about it." We need to document these discoveries.